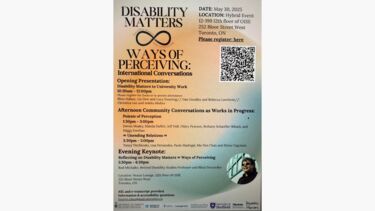

Disability Matters - Ways of Perceiving

Our Spring Institute promoted International Conversations about disability perceptions in and outside of medicine hosted by OISE, šĢ―ĮÉįĮø of Toronto, Canada in May 2025

The Spring, Summer, Winter and Autumn Disability Institutes of Disability Matters seek to showcase emerging disability studies scholarly and create forms of community that ask us to reflect, think and write together. This Spring Institute was hosted by OISE, šĢ―ĮÉįĮø of Toronto, and led by Professor Tanya Titchkosky; one of the Co-investigators of Disability Matters. Below Tanya provides some background to the event and some of the participants give their reflections on our time together

Disability Matters â Ways of Perceiving: International Conversations

May 30, 2025, OISE of the šĢ―ĮÉįĮø of Toronto

Prof. Tanya Titchkosky, Disability Studies, Department of Social Justice Education, OISE of the šĢ―ĮÉįĮø of Toronto.

Behind the scenes

Since September 2024, several resources related to disability studies in the Department of Social Justice Education at OISE came together. Dr. Devon Healey was granted a šĢ―ĮÉįĮø of Toronto, for studying cultural forms of perception, including blind perception. I (Tanya) secured a grant from the newly established at the šĢ―ĮÉįĮø of Toronto, that enabled PhD candidate Aparna Menon and I to conduct public health archival research on how disabled people were addressed in times of health crisis. Prof. Dan Goodley, in securing a large grant, Disability Matters, could bring UK disability studies researchers to OISE, and Dr. Elaine Cagulada was hired as the Toronto-based early career researcher for this initiative. These resources allowed us to plan a one-day disability studies conference at OISE.

What started as plans for a small conference, quickly grew. The desire for hybrid formats, broader participation, and expanded topics within the group was strong. After years of the Department of Social Justice Education being closed to in-person events due to COVID and then renovations, I was thrilled to host a conference again, especially with plans for creative accessibility. We set a date: May 30, 2025. Momentum grew, rooms were booked, tech was requestedâĶ and, then, the planning bug really bit; it got the better of me. I was dreaming of crowds, mugs and pens emblazoned with the conference name.

One problem: no name, no theme. All form, no content.

There was a safety line, though. Since 2006, I had been convening the Doing Disability Differently (DDD) research, reading, and activist group. At various times, this group included disability studies faculty, graduate students, post-docs, staff, sometimes undergrad students and sometimes faculty on leave from other universities. Together weâve been doing research and access activism at OISE, the šĢ―ĮÉįĮø of Toronto campus, and beyond for nearly two decades. We have hosted international speakers, reading groups, weâve done access audits of OISE space, advocated for more accessible washrooms and subway entrances as well as formulated safety and emergency plans. At least two edited DS collections are connected to the DDD ( and ). We have also hosted colloquiums, seminars, a DS Summer Institute as well as a Critical Influencers conference and intra-university sessions such as âWhatâs Up with DS in Toronto,â and âOuta Sight.â At bottom, the DDD events generate discussions that nurture the assumption that disability is not an individual problem but, rather, a collective interest that matters through all our relations.

This was my safety line. Whatever experience and exuberance I brought to organizing, it was not enough to ground the May 30th conference. Conference planning needs to include questions as to why we should gather, through what sort of orientation, and in relation to what topic or themes? DDD, I realized, was an ideal place for such questions. But another problem; the DDD group included people who had never experienced an academic conference and others who found them alienating. These divergent perspectives, along with my concern about getting captured by the organizing bug, sharpened our need to reflect on the meaning of hosting a DS conference.

Despite my white settler background, I had heard stories of how Indigenous people gathered for storytelling and thus I had imagined that there must be indigenous stories about gatherings. Finding such a story would likely allow us in DDD to begin to discuss the question, âWhy gather?â And âWhat values permit our gathering?â Guided by this understanding, I searched and found The Meeting of the Wild Animals â a Tsimshian story of the North Pacific coast of Turtle Island which is based on texts recorded by Henry W. Tate, a Tsimshian person (before proceeding, please read the story copied below or page 106-108 of ).

Reading The Meeting of the Wild Animals at the Doing Disability Differently meeting in October, 2024 put a pause on planning and gave us the opportunity to reflect on what gatherings mean and whose interests are served. Are conferences about the interests of the Big Animals, Grizzly Bear or Panther, or smaller ones such as Porcupine or Mouse, or is it the Humans (or their threats) that launch the Animals need to meet in the first place?

Discussing the story stilled my âjust do itâ attitude. The DDD group re-considered what we are after when attending conferences. For example, we wondered about those times where a meeting is more about the access rules than what those rules were made to support. Even as able-ism hunts us all down in our dens and determines the parameters of life worthy of life and its opposite, there are ways that we in DS try to freeze able-ism out, an act that might be as dangerous as unbridled able-ism. The story also suggested that experience â be it Grizzley Bearâs or Porcupineâs -- is not knowledge itself but is a beginning place from which to consider the unfolding of what is valuable. Still, it is hard not to agree with Porcupine that it is infuriating to be part of a group that attends to one set of interests as if this takes care of everyone. Still, noting that interests are always partial and tied to power, doesnât mean that rage, biting oneâs thumb off, or killing other interests are the best way to nurture ongoing relations. The discussions we had with the guidance of the The Meeting of the Wild Animals meant that whatever happened at the conference, the behind the scenes (re)orientation had already nurtured our collective relations through cultivating our commitment to questioning.

Given the story and ensuing discussion, we treated the research grants from which our conference had secured its funding as differing sets of living interests. In attempting to recognize what might lie between disability matters and ways of perceiving, we landed on the infinity sign - â -the sign for the on-going relations between our disability studies research work, and the need to consider the place of disability experience in our lives. The mutuality between disability matters and the perception of how this is so, led to the conference theme and meant we might not be tempted to ask for the coldest winter to stave of being hunted by the typical conference goal of performing productivity or biting off our thumbs in the face of ableist university ways and disabling world events. Perhaps the infinity sign â is a reminder to stay in touch with the various values and norms of the âconference seasonâ while not becoming at one with them. `

The Meeting of the Wild Animals [see footnote i below]

A long time ago, when the Tsimshian lived on the upper Skeena River, in Prairie Town, there were many people. They were the most clever and the strongest among all the people, and they were good hunters, and caught many animals, going hunting the whole year round. Therefore all the animals were in great distress on account of the hunters.

Therefore the animals held a meeting. The Grizzly Bear invited all the large animals to his house, and said to them, ''We are dis tressed, and a calamity has befallen us on account of the hunting of these people, who pursue us into our dens. Therefore it is in my mind to ask Him Who Made Us to give us more cold in winter, so that no hunter may come and kill us in our dens. Let Him Who Made Us give to our earth severe cold!" Thus spoke the Grizzly Bear to his guests. Then all the large animals agreed to what the chief had said, and the Wolf spoke: "I have something to say. Let us unite all the small animals,âeven such as Porcupine,' Beaver, Raccoon, Marten, Mink, down to the small animals such as the Mouse, and the Insects that move on the earth,âfor they might come forth and protest against us, and our advice might come to nought!" Thus spoke the large Wolf to the large animals in their council.

Therefore on the following day the large animals assembled on an extensive prairie, and they called all the small animals, down to the insects; and all the small animals and the insects assembled and sat down on one side of the plain, and the large animals were sitting on the other side of the plain. Panther came. Grizzly Bear, Black Bear, Wolf, Elk, Reindeer, Wolvereneâall kinds of large animals. Then the chief speaker, Grizzly Bear, arose, and said, "Friends, I will tell you about my experiences." Thus bespoke to the small animals and to the insects. "You know very well how we are afflicted by the people who hunt us on mountains and hills, even pursuing us into our dens. Therefore, my brothers, we have assembled (he meant the large animals). On the previous day I called them all, and I told them what I had in my mind. I said, 'Let us ask Him Who Made Us to give to our earth cold winters, colder than ever, so that the people who hunt us can not come to our dens and kill us and you!' and my brothers agreed. Therefore we have called you, and we tell you about our council." Thus spoke the Grizzly Bear. Moreover, he said, "Now I will ask you, large animals, is this so?"

Then the Panther spoke, and said, "I fully agree to this wise counsel," and all the large animals agreed. Then the Grizzly Bear 1 (107) turned to the small animals, who were seated on one side of the prairie, and said, ''We want to know what you have to say of this matter." Then the small animals kept quiet, and did not reply to the question. After they had been silent for a while, one of their speakers, Porcupine, arose, and said, "Friends, let me say a word or two to answer your question. Your counsel is very good for yourselves, for you have plenty of warm fur, even for the most severe cold, but look down upon these little insects. They have no fur to warm themselves in winter; and how can small insects and other small animals obtain provisions if you ask for severe cold in winter? Therefore I say this, don't ask for the greatest cold." Then he stopped speaking and sat down.

Then Grizzly Bear arose, and said, "We will not pay any attention to what Porcupine says, for all the large animals agree." Therefore he turned his head toward the large animals, and said, "Did you agree when we asked for the severest cold on earth?" and all the large animals replied, "We all consented. We do not care for what Porcupine has said."

Then the same speaker arose again, and said, "Now, listen once more! I will ask you just one question." Thus spoke Porcupine "How will you obtain plants to eat if you ask for very severe cold? And if it is so cold, the roots of all the wild berries will be withered and frozen, and all the plants of the prairie will wither away, owing to the frost of winter. How will you be able to get food? You are large animals, and you always walk about among the mountains wanting something to eat. Now, if your request is granted for severe cold every winter, you will die of starvation in spring or in summer; but we shall live, for we live on the bark of trees, and our smallest persons find their food in the gum of trees, and the smallest insects find their food in the earth."

After he had spoken. Porcupine put his thumb into his mouth and bit it off, and said, "Confound it!" and threw his thumb out of his mouth to show the large animals how clever he was, and sat down again, full of rage. Therefore the hand of the porcupine has only four fingers, no thumb. All the large animals were speechless, because they wondered at the wisdom of Porcupine. Finally Grizzly Bear arose, and said "It is true what you have said." Thus spoke Grizzly Bear to Porcupine, and all the large animals chose Porcupine to be their* wise man and to be the first among all the small animals; and they all agreed that the cold in winter should be as much as it is now. They made six months for the winter and six months for summer.

Then Porcupine spoke again out of his wisdom, and said, "In winter we shall have ice and snow. In spring we shall have showers of rain, and the plants shall be green. In summer we shall have warmer weather, and all the fishes shall go up the rivers. In the fall the leaves shall fall; it shall rain, and the rivers and brooks shall overflow their banks. Then all the animals, large and small, and those that creep on the ground, shall go into their dens and hide themselves for six months." Thus spoke the wise Porcupine to all the animals. Then they all agreed to what Porcupine had proposed.

They all joyfully went to their own homes. Thus it happens that all the wild animals take to their dens in winter, and that all the large animals are in their dens in winter. Only Porcupine does not hide in a den in winter, but goes about visiting his neighbors, all the different kinds of animals that go to their dens, large animals as well as small ones. The large animals refused the advice that Porcupine gave; and Porcupine was full of rage, went to those animals that had slighted him, and struck them with the quills of his tail, and the large animals were killed by them. Therefore all the animals are afraid of Porcupine to this day. That is the end.

i. This story resembles, in the form of the speeches, the story of TxamsEm's war on the South Wind, p. 79, and has been influenced in form by the Kwakiutl tales. The term "He Who Made Us" is presumably due to Christian influence.

Various myths and stories of the Tsmimshin people were collected by Franz Boas (for the US government around 1909 to 1910) and published in Thirty-First Annual Report of The Bureau of American Ethnology to The Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution 1909-1910; Washington Government Printing Office 1916, page 106 -108.

Disability Matters âŊâ âŊWays of Perceiving: International Conversations

by Mu-Yen Chan, PhD Student and Presenter, Social Justice Education, OISE of the šĢ―ĮÉįĮø of Toronto

At the morning panel of the Disability Matters: Ways of Perceiving conference, Dr. Tanya Titchkosky, in her opening reflection, reimagined the infinity symbol (â) not as a scientific abstraction, but as a symbol of relationality rooted in Anishinaabe worldviews. Dr. Titchkosky invited the audience to think of disability and perception as infinitely connected. Building on this, Dr. Dan Goodley and Dr. Rebecca Lawthom used Thomas Kingâs image of pushing a boat back into the ocean to describe their efforts to push back against university bureaucracy while co-producing knowledge with disabled peopleâs organizations, fostering community through friction. They proposed âfrictional politicsâ as both an analytic and a method for de-pathologizing academic spaces. Christina Lee and Ankita Mishra added a powerful critique of current models of knowledge exchange, arguing that disabled communities already share valuable forms of knowledge in daily lifeâthrough mutual care, access coordination, and storytellingâdespite such knowledge being undervalued or ignored by academic metrics. Together, the speakers responded to Dr. Titchkoskyâs reimagining of the infinity symbol, offering a living and ongoing practice of relationality, resistance, and care within and beyond the university.

During the relaxed lunchtime session, Dr. Leroy Baker and Dr. Dan Goodley shared brief but thought-provoking book presentations. Dr. Baker introduced Navigating Complexities: The Intersectionality of Blackness and Disability in Higher Education, drawing from his experiences of childhood trauma in Jamaica and systemic racism in Canada. He emphasized education as a tool for critiquing structural injustice and called for rethinking âaccommodationâ to foster truly inclusive academic spaces. Dr. Goodley presented the third edition of Disability Studies: An Interdisciplinary Introduction, highlighting the diverse and evolving directions of disability studies.

In the afternoon, one of the two âCommunity Conversations as Works in Progressâ sessionsâtitled The Poiesis of Perceptionâfeatured four speakers: Miggy Esteban, Matida Daffeh, Jeff Hall, and Hilary Pearson. Each offered deeply personal stories that reimagined perception not as passive sensing, but as poiesisâa creative, embodied process. Matida reflected on the âwhispersâ surrounding her deaf son in Gambian society, showing how care, protection, and stigma were entangled in subtle forms of everyday perception. Jeff revisited his adolescent reaction to the Tracy Latimer case, uncovering how ableist media narratives taught him to grieve some lives less than others. Hilary shared her experience of being seen as an âunreliable witnessâ in legal contexts due to hearing loss, revealing how institutional systems question disabled credibility. Miggy redefined rest as a radical, mad, diasporic gestureâwhere stillness becomes resistance to normative rhythms. Across all four narratives, disability was not framed as a lack or a tragedy, but as a generative site of knowledge, relation, and poetic insight.

In the Unending Relations session, introduced by Dr. Tanya Titchkosky, the infinity sign (â) was used as a metaphor to explore the non-linear, entangled relationship between disability and medicine. Rather than framing these as oppositional forces, the session invited us to consider how all things are interconnected through complex interrelation. Lisa Fernandez examined how the term disability is absent from the Deanâs Reports and undergraduate course calendar at the Temerty Faculty of Medicine, revealing a cultural imaginary where disability is rendered unmentionable in medical education. Paola Madrigal shared the encounter with Mad Studies in a public health course, which challenged dominant psychiatric narratives and invited relational, critical thinking about madness. Mu-Yen Chan explored what happens when medical doctors are also disabled, highlighting the cultural tension between expectations of professional capability and assumptions of dependency. In closing, Dr. Elaine Cagulada reminded us that repetition is not failure, but a form of consciousnessâone that invites us to return to and question our assumptions. Dr. Cagulada urged us to recognize that medicine and disability are not separate realms but are deeply interwoven, calling us to dwell within this tension and engage our collective lives more attentively.

In the closing keynote, retired Disability Studies professor and blind storyteller Dr. Rod Michalko offered a profound reflection on the lived and conceptual dimensions of disability. Drawing from his experiences as a blind academic and decades of scholarship, he described disability not as something one seeks, but as something one âstumbles intoââa metaphor for the unexpected and disruptive nature of encountering disability in everyday life. Challenging simplistic narratives, he quoted musician Rhiannon Giddens: âSimple stories are usually wrongâand not good for you.â Rather than rushing to fix or define disability, Dr. Michalko encouraged listeners to pause, hesitate, and approach disability as a teacherâone that invites us to reimagine how we know and relate to the world. Quoting Tanya Titchkosky, he emphasized that accessibility is not merely about logistics but involves socio-political judgments about participation and belonging. Drawing on Rosie Braidottiâs reflections on Sandra Harding, he framed disability experience as a site of epistemological inquiry. His keynote did not conclude with definitive answers but extended an invitation: to stay with the discomfort of uncertainty, and to learn from the stumble rather than leaping over it.

Disability Matters May 30th 2025 Reflection

by Dr. Maria Karmiris, Elementary Teacher, Toronto District School Board; Sessional Lecturer OISE, šĢ―ĮÉįĮø of Toronto; and Sessional Lecturer, Toronto Metropolitan šĢ―ĮÉįĮø.

From the initial entry point into Disability Matters as shared by Tanya Titchkosky, it was a day full of exploring disability as intentionally frictional. This understanding of disability as intentional frictional was offered by Goodley and Lawthom as they explored the distinct yet linked necessities of engaging in practices of decolonization and depathologization. To me this seemed to be the key theme explored by all of the presenters throughout the day.

I was particularly struck with the discussion around access points when juxtaposed with the land acknowledgment which was pivotal to Tanyaâs introduction into Disability Matters. In the location where the Disability Matters conference occurred, there are inescapable legacies of the making and subsequent breaking of treaties with indigenous peoples. was a promise of reciprocal relation that was made and then broken.

Access points and the current role of technology as a medium for both making and breaking access points of potentially reciprocal relations kept bubbling up throughout the day. Cameras for video conferencing were positioned and repositioned. This occurred alongside the repositioning of microphones that were too close for some and too far for others as well as ASL interpreters who kept repositioning themselves for the purpose of sustaining access points. These movements and motions served as a reminder of the always and already frail and uncertain conditions of access to and in reciprocal relations.

The image of a dish with one spoon also reminds me of story from my childhood. My mother and father were born at the end of World War II and in the middle of a Greek Civil War that pitted communities and even families against each other. In my childhood my parents shared memories of their own childhood where some families literally shared a dish with one spoon and passed it around the so everyone would have something to eat. This memory from listening to stories as a child, reminds me that a dish with one spoon is both a metaphor of reciprocal relations as well as materially and tangibly vital to survival with and for each other.

Access points are not add-ons but integral to survival in material, tangible and everyday ways. Access points require the ongoing and necessarily frictional work of sustaining them. Each presenter in their own way addressed and explored the simultaneous necessity and frailty of access points in ways that made disability matter.

âIndinawemaaganidogâ and âVasudhaivam Kutumbakamâ: Stumbling into Infinite Relationality

Aparna Raghu Menon, Ph.D. Candidate

Dalla Lana School of Public Health, šĢ―ĮÉįĮø of Toronto

Working as I do, in a disability studies framework informed by posthumanism, I think a lot about relationality. My view of disability is informed by my belief that Western Enlightenment valorizations of individualism, agency, rationalism, intentionality, and independence are limited, reductive, and ultimately ableist theorizations of the world and the various disabled and non-disabled humans and non-humans that inhabit it. My beliefs on relationality are also entangled with a part of my identity. As a brown /immigrant and an uninvited guest on Indigenous lands, my cultural heritage has introduced me to the idea of Vasudhaivam Kutumbakam, a Sanskrit phrase found in the Upanishads that loosely translates to âthe world is my familyâ. Our day-long conference takes place on traditional lands of the Huron-Wendat, the Senecas and the Mississaugas of the Credit River. The language of the Mississaugas, Anishinaabemowin, offers us - without expectation of any return - a phrase known as Indinawemaaganidog. This translates to "I am all my relatives, and all my relatives are me" (Vukelich, 2023, p.31). The noun form of ârelativesâ is ârelations.â And, I cannot help but be struck by the relationality of this phrase to Vasudhaivam Kutumbakam.

But what do these ideas have to do with our conference?

It is the evening of the conference. Rod Michalko, disability scholar, retired professor, and Gentle Teacher, is delivering the keynote. Rod speaks of the many stumblings with which we become entangled with disability. He takes us into Nietzscheâs theorizings on how the world remains senseless until we bind perception to existence. At that moment, with the setting sun streaming into the room and listening to him, I experience Indinawemaaganidog. I, too, am binding my perception of relationality to my existence. As he speaks, I watch myself embedded in an expansive network of relationships â historical, present, and future. Vasudhaivam Kutumbakam. I, an uninvited I/immigrant on these lands, was an invitee to the conference. I listened to speakers I had heard before and speakers from England whom I heard for the first time. I watched a D/deaf participant nod and smile as she engaged in a relational act of understanding with the ASL interpreters. I cried uncontrollably as a speaker shared the story of Tracey Latimer. Tracy Latimer was my disabled, autistic seven-year-old son, Vikram, and my seven-year-old son was Tracy Latimer. As Tanya Titchkosky, disability scholar and Gentle Teacher, opened the conference, talking of the infinity sign, I travelled back and forth from past to present to hear her voice speaking during Critical Disability Studies courses during my MA in 2021.

Via these moments, I see myself embedded in an expansive network of relationships within the room â bound by deep love and affection to many in the room, bound by caring and respect to others, bound by dependence to a tech team I do not know but whose kindness and expertise support much of the day, bound by experiencing, reading, writing and talking disability. Relationships not just with the people in the room but with their scholarship, health, love, care, beliefs, and with time itself.

As the sky outside moves into dusk, I experience an embedding so dense that I cannot even discern the texture of its weave or discern one dimension of existence from another. I am a philosophical existence within Nietzsche-Rodâs words, I am an imaginary existence as in the case of Tracey-Vikram, and I also exist as a tangible body-mind in a collection of body-minds grouped in the Nexus Room in OISE on occupied land. All these existences, real or imaginary, present, past or future, are validâĶand interdependent. Posthumanist thought talks of âbecoming-with.â I experience that moment of becoming-with disability in these relational existences. The world is my family. Vasudhaivam Kutumbakam.

Why do I think this relational experience is vital for my thinking on disability studies?

Because the embedding that I speak of troubles the notion that separation is a necessary part of teasing out theoretical truths from disability experiences. That we need this distance to arrive at pure epistemological insights. Closeness hinders, says this WEIRD-centric worldview. We need to step back to see and discern normalized structures â to distil the potency of a lived experience of a disability. But what if we embrace closeness and a relationality that refuses to separate? Does that mean we loosen our grip on reality? Maybe not. Maybe what we loosen our grip on is not reality, but intentionality, surrendering instead to shared lived experiences of disability that are so integral to our own self that we become-with them. We stumble in and out of different contexts - mine, yours, ours, real, imaginary. We are affected ontologically, if you will, in a hundred, thousand, infinite ways. I am them; they are me. Indinawemaaganidog.

Citations

Kaagegaabaw, J. V. (2023). The seven generations and the seven grandfather teachings (M. Fairbanks, Ed.). James Vukelich.

iHuman

How we understand being âhumanâ differs between disciplines and has changed radically over time. We are living in an age marked by rapid growth in knowledge about the human body and brain, and new technologies with the potential to change them.